The Song dynasty was founded in 960AD following 60 years of turmoil after the fall of the Tang, China’s golden age. Like the Tang, it was a great era of garden building. It was a time of commercial prosperity, scientific and technological advancement, agricultural development and, as a consequence, population expansion. However, with powerful rivals to the north and west, contested borders, factionalism at court and the long shadow of the An Lushan Rebellion (which broke the power of the Tang) behind it, Song prosperity was tinged with hedonism and excess.

The eighth Emperor of the Northern Song was Huizong (1082-1135AD). He was a great painter – arguably one of China’s greatest – a calligrapher, a musician and poet. He wrote treatises on medicine and on tea. He was a patron of the arts, a fervent Daoist, an avid collector of paintings and antiques, and passionate about gardens. In particular, he loved rocks.

There were five Imperial parks in the Song capital Bianjing (now Kaifeng), four of which were situated at the gates on the four sides of the city. These parks were opened to courtiers and officials on set occasions, and one was opened to the general public for a short while each year. The fifth park, Genyue, the Northeast Marchmount, was for the private use of the Emperor and his guests. It was built beside the imperial residence on a site selected by a geomancer in the northeast of the city. He recommended that the earth be heaped up and artificial mountains constructed, to ensure the Emperor plenty of heirs. (The character ‘Gen’ 艮 of Genyue is from the I Ching and represents mountains, the northeast, and sons).

The construction of Genyue was, after long preparation, begun in 1118, but Huizong had been collecting plants, rocks, animals, and birds from much earlier in his reign. In 1105 a ‘Provision Bureau’ was set up in Suzhou. This was the base of the merchant Zhu Mian, who was especially talented at finding scarce and valuable Lake Tai stones, often in other people’s gardens. Some of these ended up in Zhu Mian’s own garden. To find materials for Genyue a ‘Flower and Rock Network’ was set up to transport huge quantities of rarities from all corners of the empire. The scale of this undertaking is hard to comprehend. Collectors sourced rare plants from as far as 900 miles to the south of the capital. The military were drafted in to help with transportation, and commoners were sent out to search in swamps and mountains for rare plants. A dedicated fleet of boats transported huge rocks along the Grand Canal to the capital, day and night, interrupting the normal transport of food and raw materials. In some places bridges were knocked down and irrigation systems destroyed to allow their passage. As well as the physical damage and disruption, the Flower and Rock Network spawned largescale corruption and waste, drained the imperial treasury, and was greatly resented by the common people.

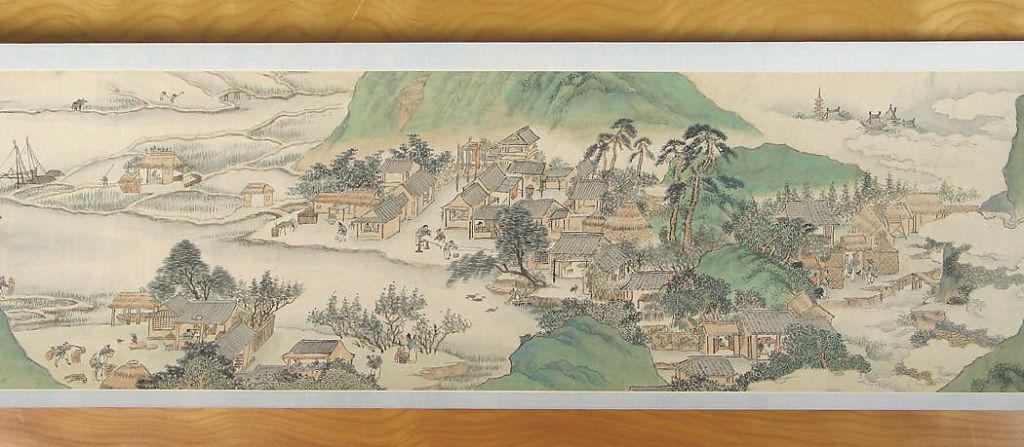

Completed in 1122, Genyue was a representation of the empire in miniature, a tradition dating back to earlier Emperors, most notably Qin Shi Huangdi himself. Depleting an empire to build a garden seems supremely frivolous now, but at the time such gardens had a ritual and religious aspect, giving the project a deeper meaning. As well as ensuring more sons, Huizong hoped to gain the favour of the Immortals for himself, his dynasty, and for Song China. Zhang Hao, an official writing soon after the events, during the Southern Song, recounted the story of the site’s geomantic significance:

…as predicted, there was a response [in the form] of numerous sons. From this time forward, there was regular security within the seas and lack of incident at the imperial court, and His Highness devoted quite a bit of attention to parks and preserves.

Record of the Northern Marchmount, Zhang Hao, translated by James M. Hargett p. 185 in The Dunbarton Oaks Anthology Of Chinese Garden Literature, A. Hardie and D.M. Campbell (Eds,)

The garden was not particularly large, when compared to other imperial parks. What was most remarkable about it was the size of the artificial mountain landscape,

…an artificial pile more than ten li in circumference, of ‘ten thousand layered peaks’, with ranges, cliffs, deep gullies, escarpments and chasms. In some places the structure rose two hundred and twenty-five feet above the surrounding countryside, and in others it fell away, through foothills of excavated earth and rubble, to ponds and streams and thickly planted orchards of plum and apricot.

The Chinese Garden, Maggie Keswick, p.53. ‘Li‘ is a historical measurement which has varied over time. In the Song dynasty, ten li was about 2.5 miles.

There were dozens of buildings dotted about this landscape, enumerated and named by the Emperor in his own account of the garden. There was an artificial cascade, operated by workers who rushed to open the sluice gate when the Emperor arrived. More prosaically, there was a farm with fields, orchards, and a herb garden. Besides entire transplanted forests of bamboo there were plants of all kinds. Huizong himself records some of the plants that were sent from around the empire.

…loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), orange (Citrus sinensis),

Record of the Northern Marchmount, Emperor Huizong, translated by James M. Hargett ibid p.186

pomelo (Citrus grandis), sourpeel tangerine (Citrus deliciosa),

sweetpeel tangerine (Citrus reticulata), betel-nut palm (Areca catechu),

Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis), and lichee (Litchi chinensis)

trees, as well as gold moth (unidentified), jade bashfulness

(unidentified), tiger ear (Saxifraga stolonifera), phoenix tail

(Pteris multifida), jasmine (Jasminum grandiflorum), oleander

(Nerium oleander), Indian jasmine (Jasminum sambac), and magnolia

(Michelia figo) plants. Ignoring variations in geography and differences

in climate, all the trees and plants generated and grew…

Above all, of course, there were rocks. Scholars’ rocks had become popular in gardens in the Tang dynasty, but Huizong took petromania to new extremes. Fantastically shaped rocks were arranged all over the garden. Names were bestowed upon them, and engraved, with the most important inscribed in gold.

Unfortunately, the use of the vast amounts of money and manpower expended on the garden weakened an empire surrounded by warlike rivals. Focusing on his garden and the arts, Huizong neglected economic policy and, most crucially, the military. In 1126 – just four years after Genyue was completed – the Jurchen, of the Jin empire to the north, laid siege to Bianjing. The garden was destroyed, its precious rocks flung from catapults, its trees cut for firewood, its rare animals killed and eaten by the army. Huizong was persuaded to abdicate in favour of his son. A temporary peace was cobbled together, but within a year, the Jurchen returned in greater force. They took Bianjing, sacked the city, destroyed or looted its treasures, and massacred many of the inhabitants. Huizong was taken north as a captive, given the mocking title Duke Hunde ‘Besotted Duke’. One of his sons, who avoided capture, withdrew south of the Yangtze and founded the Southern Song. Huizong died in Heilongjiang in 1135, a prisoner of the Jin dynasty to whom he had lost the heartlands of his country.