In the classical Chinese garden, sound was an essential element. The garden is a representation of nature in miniature, and that includes the evocative sounds of the Chinese landscape. Borrowed scenery is an important concept in the Chinese garden and in The Craft of Gardens, Ji Cheng discusses it at length. Borrowed scenery refers not just to views of landscapes outside the garden, but to other elements which can be brought in, such as sounds, fragrances, and wildlife.

Planting flowers serves to invite butterflies, piling up rocks serves to invite clouds, planting pine trees serves to invite the wind… planting banana trees serves to invite the rain, and planting willow trees serves to invite cicadas.

Zhang Chao (1650-1707)

Plants, chosen for their symbolic meanings as well as aesthetic effect, were often used to create sounds. Bamboo is one of the essential plants of the Chinese garden, representing spring, and symbolising the virtues of the Confucian gentleman – such as humility, resilience, and uprightness. The sound of the wind blowing through bamboo leaves was known as ‘the sound of heaven’, and pavilions would be sited to take advantage of this effect. It was also compared to tinkling pieces of jade. There is a story that one of the Sui empresses could not sleep without the sound of bamboo, so the emperor order courtiers to hang jade pendants from the eaves to mimic the sound.

The effect of wind in the pines was called songtao 松涛, often translated as ‘pine wind’ but ‘pine waves’ or ‘pine surf’ might be better. Large areas of pines were planted where space allowed, at the Summer Palace in Chengde, for example. In smaller gardens a single pine could evoke this.

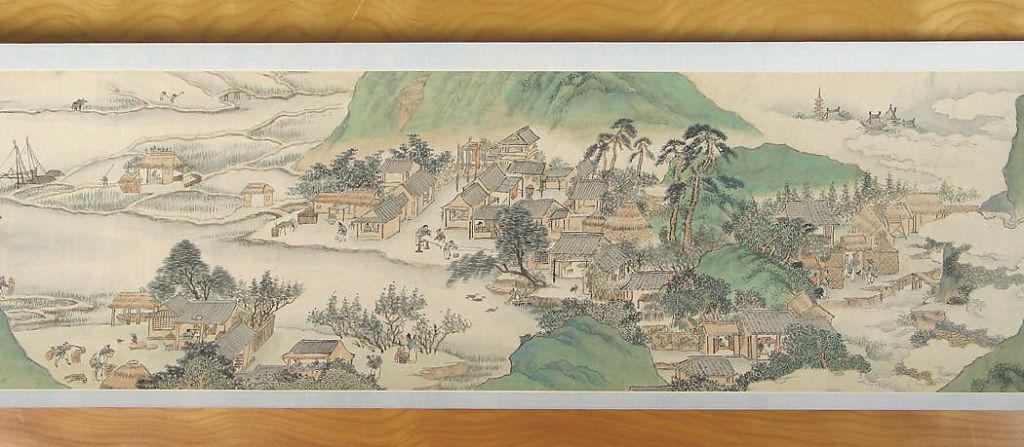

‘Wind through the pines’ is a phrase found in a number of poems and songs, and is also represented in paintings. Pine is another highly symbolic plant, associated with strength, resilience, and long life.

Large leaved plants such as banana and lotus were valued for the sound of rain falling on their leaves. Bamboo leaves are prone to being shredded by the wind, so to protect them they were often planted in clumps against a sheltering wall, against which their shadows moved. A pavilion would be built nearby with windows looking out onto the bananas to enjoy the aesthetic effect, both visual and auditory.

The pattering of rain on withered lotus leaves was a theme often used in poetry to create a feeling of melancholy, and was particularly associated with autumn. The Listening-to-the-rain Pavilion in the Humble Administrator’s Garden, Suzhou, was placed to highlight the different sounds of rain on various types of leaves.

Other natural sounds were produced by birds, animals, and insects. The song of Orioles was particularly admired, and willows in particular were planted to attract them. This association was also used in paintings and poems, perhaps most notably this by the great Tang poet Du Fu.

Two golden orioles sing in the green willows,

A row of white egrets against the blue sky.

The window frames the western hills’ snow of a thousand autumns,

At the door is moored, from eastern Wu, a boat of ten thousand li.Jueju (Two Golden orioles Sing in the Green Willows) by Du Fu, translation from chinese-poems.com

Willows were also associated with cicadas, one of the sounds of summer, and a symbol of rebirth and the cycle of life and death. As they were believed to live solely upon dew, cicadas also represented a pure and refined life.

Finally, sounds in the garden could be artificial – music, singing, nearby temple bells or prayers. Occasionally, elements of the garden would be built to produce sounds, although this is not as common as it is in Japanese gardens. One example of this is Winter Hill in Geyuan garden in Yangzhou, which has a wall with 24 round holes in it, through which the wind blows. This makes noises reminiscent of winter storms. (This section of the garden also faces north so it gets no direct sunlight and has white quartzite rocks to evoke the effect of snowy mountains).

As with everything else in the Chinese garden, sounds existed in balance and harmony with their opposite, silence.

The forest is more peaceful while cicadas are chirping. The mountain is more secluded while the birds are singing”

Wang Ji